An Interview with Valérie Lamontagne

Valérie Lamontagne is a digital media artist, designer, theorist and curator based in Montréal, Canada researching techno-artistic frameworks that combine human/nonhuman subjects. She recently used Max/MSP in a performance based on the Charles Perrault fairy tale “Peau d’Âne.”

In it, a young princess, whose kingdom’s riches are dependent on a gold excreting donkey, orders the impossible from her doting stepfather to thwart marrying him: three dresses made of immaterial materials. The first is to be made of the “sky” and should be as light and airy as the clouds. The second is to be made of “moonbeams” and should reflect the same lyrical intensity as the moon at night. The third, and last, is to be made of “sunlight” and should be as blinding and warm as the sun above.

Can you tell me a little about your background?

My background is in visual arts. I studied art history and fine arts. I did an MFA, a Master of Fine Arts, in painting.

Where was that?

That was at Concordia University in Montréal, both at the undergraduate and the graduate level. I'm presently enrolled in a Ph.D., also at Concordia, researching “Performativity, Materiality and Laboratory Practices in Artistic Wearables.” So I've been there for a while.

Are you from Montréal?

I'm French Canadian, so I was born in Montréal. However, my parents were hippies, and worked in theater, and then in film. They both did design and technical direction. This made for a lot of moving. I lived back and forth between English and French Canada, and the U.S. and Canada. In the U.S., we lived in Minneapolis, because the Guthrie Theater. We also lived in North Carolina for a while, while mother did an MFA at the North Carolina School of the Arts and where I later enrolled and studied acting for one year -- I was a terrible actress.

So you were brought up in a really artistic household?

Yes, it was exceptionally artsy. In my early twenties I was rather critical of the theatre and thought: "This is not real art, because you're working for a company, and you don't have the autonomy of creative genius." But now that I work in new media, and it's all about teams, of course I don't think that way any more about creative and collaborative endeavors.

The theater is a great context to learn about building stuff and presenting technology with people in a performative context. What I'm doing now, in terms of wearable art, involving the body, goes back to that. I’m looking at performance, performativity, and how the presentation context can add to the live-ness of interactive artworks. Also, for me, technology is performative.

But you started your MFA as a painter?

For the MFA, I enrolled in painting, but I ended up doing performance. I did relational performance, which had an important component on the Internet as confessionals or portals for exchanges. This was in 1999/2000, so people were just beginning to do really creative interventions on the Internet -- in fact the Internet was a very performative medium at that time, like e-toys or Mouchette. People were ‘posing’ as all kinds of things, because the web can mask identity, so identity is always constructed.

In fact, it was through these on and offline performances that I ended up making the Peau d'Ane project. I was doing a lot of performances that involved the costume as the key element to the performance. The performance that I did for my MFA thesis show was called The Advice Bunny. I dressed up as a bunny, and I gave advice, sort of like Lucy in Peanuts. [Laughs] There was an online forum and web site where people could ask for advice as well as a ‘psychoanalytical’ consultation office.

My performances of that era were focused on framing interaction with individuals, either on line or in real life contexts, where I would set up offices, and booths, and people could come and meet with me. For example, I did another performance about a nurse unlocking the public’s sensory perception through a series of props that were used on the public -- scented oils, picture books, sandpaper etc. So again, sort of an incarnation, a sort of persona. I also did a performance based on Hans Christian Andersen's Snow Queen, which involved making snowflakes in a very large installation with about 2,000 hand cut snowflakes decorating the space as a context for making snowflakes for the public as a performance.

Working with relational performances which focused on exchanges led me to wanting to make a costume, which would have its own interactivity. I am interested in the agency of objects, and their ability to perform -- not just us -- and I wanted to explore a format which would bring the technology and the body together in a performance context. Wearables, because they are garments, have that potential to phenomenologically transform us -- through technology. This is and remains very interesting to me. I remembered a fairy tale called Peau d'Ane [Donkey Skin], which had three fantastic dresses -- one could even call them impossible dresses -- made of the moon, sun, and sky. In the fairy tale the princess requests them as a test in order to avoid marrying her own father. Clearly she believes that they cannot be made, though they are made! I thought: Wouldn't it be great to make them? To make them really interact with these components? So, I made a Moon, Sun, and Sky dress.

I began doing research in wearable, smart textiles technologies and materials, and looking into ways of creating an interaction between the garment and the environment. It was the meeting of this fairy tale, and relational performances involving costumes, which led to Peau d’Ane.

How were you introduced to Max/MSP?

I took a class at a women’s media centre in Montreal called Studio XX and I ended up enlisting my teacher, Patrice Coulombe, to help me. It was an interesting exchange because he was interested in learning more about physical computing, and I was just beginning doing research in that area. Tom Igoe and Dan O’Sullivan’s book Physical Computing: Sensing and Controlling the Physical World with Computers had just come out, so this was a new area of exploration that was becoming more accessible for artists. Patrice really collaborated quite significantly for the Max/MSP components of the project. There are layers of complexity that I couldn't really deal with, and that even Patrice didn't know a whole lot about at the start of the project. We explored the project together over almost 3 years. Also an engineer / artist, David Beaulieu worked on the electronics in later stages of the project to create customized circuits.

For the wearables, I am now working mostly with Arduino, and more specifically the LilyPad Arduino. At the time of the Peau d’Ane project we were using a charlieplexing chip which had not been integrated into the Arduino toolbox, so we had to design our own circuits. In fact, Arduino didn’t even exist when we started the project.

What is Arduino?

Arduino is an open-source electronics prototyping platform. A company called Arduino in Italy makes them and they have really democratized the field of electronics for artists by making circuits which are easily programmable and designed for artist / interaction designer’s use. For people who are interested in physical computing, they've packaged a series of components, and circuit boards to build your own micro-controllers. They could be used for stand-alone work or they can communicate with software, like Max/MSP.

Specifically Leah Buechley, now at the High-Low Tech Group at MIT, designed a circuit and a series of sensors / LEDs etc, which are made for wearables. The design of the circuits are adaptable to the use of other wearables materials such as conductive threads and materials. The Arduino programming language (called Wiring is based on Processing) is very simple and very well documented -- kind of like Max/MSP! That being said, it’s always possible to design your own circuits. I am not necessarily pro-Arduino -- I always encourage my students to start by making their own circuits, it’s much cheaper and you learn a lot more -- Arduino just makes it quick and accessible and is very stable.

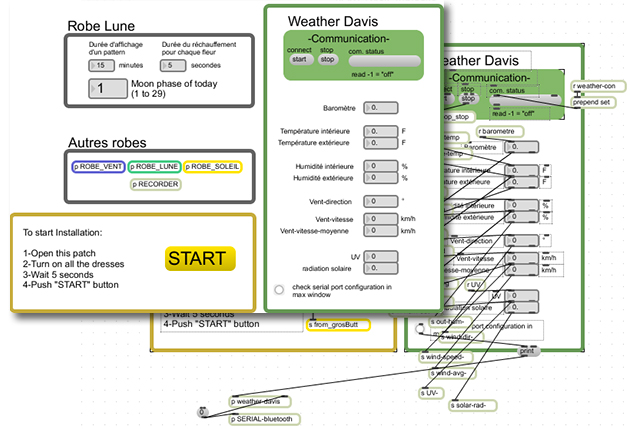

However, in the case of Peau d'Ane, because we were interpreting specific environmental data, we needed a solution for i/o. There's a small weather station, made by a company called Davis, which is for weather enthusiasts. The great thing about it is that it functions wirelessly. So we are able to have a console that could be plugged into a main computer, and then the Max/MSP patch took the incoming data from this particular console.

In the case of the Sun dress, you have input from the UV index, solar radiation, and temperature. The Sky patch interprets data from wind velocity, and wind direction. For the Moon, we programmed it to represent the 28-day cycle, without the need for the Davis console, of the moon by activating a series of 14 flowers which increased in activity for 14 days and then decrease for the next 14 days -- following the waning and growing moon.

What's interesting about working with the weather is that is very site and time specific. I live in Montréal, so there's a radical difference between the kinds of readings you're going to get in the winter versus summer. I've also traveled with this project to Peru and to Europe, so depending where you are at different times of the year, you're going to get really fluctuating readings. So the question came up: “how do you build something which can accommodate all these differences?”

For example, in Peru, it was sunny all the time. If you have your parameters set for a certain UV index; it may reach a certain level and then stops transforming itself because it hasn’t been programmed to be sensitive to small changes with a high UV/temperature range. So it might always be within a certain range, and not as active, or responsive as it might be in a different environment. We learned that parameters had to be adjusted accordingly for every climate.

So can you reprogram it on-site?

Yes. The patch is made in such a way that the outputs can be reconfigured at all times, so I can readjust them on the fly. Let's say I presented the Sun dress, in Ghent [Belgium] at one point, and it was really only sunny for one morning. I clearly would have to rethink what the parameters of the reading of the dress would be. We encountered that scenario the first time I presented the project at the Vooruit.

What we did was adjust the parameters so very small fluctuations in temperature would trigger the dress to react. The Sun dress has 128 LEDs, so what it does, in essence, is that the moment that there's a change in the Davis device readings, based on these three different parameters -- the UV index, solar radiation, or temperature -- it will begin to ‘play’ a different sequence of LEDs, and it will continue to play that sequence in a loop until there is a change in one of the three inputs. So that's why one has to research what the weather is like in that particular location if you want the dress to do something interesting. Otherwise it could just stay stuck in one parameter, and not really do anything more.

And the same goes for the Wind. Some cities are windier, or some times of the year are more dynamic. You want to program it to have the parameters be within the range of what the weather is in that particular area, otherwise, it's just not that exciting -- not that the weather is particularly exciting -- but the goal is to also create an artistic experience, so we have to ‘tweak reality’ at some levels.

In terms of technology inside of it, the Sky dress has small ventilators, and electronic components blowing into the dress, so that's how it inflates. One of the things that I wanted to do with it was to also have it aspirate, so that it could deflate. But unfortunately, the hardware that I used wasn't able to accommodate for that.

The Moon dress uses thermochromic inks, with resistive heating, so when you run the electricity through the threads, it heats up the paint, and that makes it change color. For all three dresses, the interior and exterior, all of the circuitry is made with conductive threads. The wireless communication is an ICSB, so that's how it's communicating the data with the computer.

What Max/MSP does is that it permits us to play with the programming, to observe the data coming from the weather console and create events, which we feel are interesting and dynamic enough to represent the weather fluctuations in that particular location.

How about the dresses themselves, did you design and sew them?

I worked with a fashion designer, Lynn van Gastel, to build the dresses. I had design ideas, but she had more technical experience in terms of building garments. We were looking at dresses and designs from the Twenties, so early Coco Chanel, or Madeleine Vionnet, designers who were really avant-garde for their era -- such as Sonia Delaunay -- were quite influential.

The Twenties were an exciting period -- it was the beginning of industrialization and technological advancements in textiles. They used a lot of graphic modern elements, so that's why, for example, the Sun dress has these chunky components to it, different chunks of colors. The Sky dress is a little bit more princess-y, because it blows up, but it seemed to make sense that if you're going to use the wind, you had to make something that was going to get really big. The Sky dress was in fact inspired by the late Alexander McQueen.

So it was a combination of the aesthetics that I was interested in, and the technical parameters. What is possible to make these dresses be both technically and aesthetically compelling?

Do you think you will continue using Max/MSP on future projects?

Yes, I would like to. In the department that I teach in, Design & Computation Arts at Concordia University, I always direct my students Max/MSP as a really exciting platform to do things, and not just for audio.

The limitation that I have with the wearables work that I am doing now, though, is that I'm trying to integrate all of the computation, and all of the circuits, into the garment. But Max/MSP, of course, is all in the computer, so that forces you to always deal with wireless communication. To be honest, in terms of the Peau d’Ane project, the wireless communication is the weakest link, because it's the one part that can really mess up. If the communication isn't working, then the garment can't work.

So that's why I've ended up using the LilyPad Arduinos. Of course Max/MSP is so much more sophisticated, and so much more versatile, in terms of producing things that can be transformed or adjusted in real time. I've done real time performance things with the dresses, since I have this interest in performance. I’ve played with the Max/MSP patch, transforming them in real time while someone wears them. And you can't do that if you've just programmed a chip to only do only one thing.

I think Max/MSP has the most flexibility, in terms of doing things creatively. But as I said, the worrisome thing is always the wireless communication. I’m looking into mobile phone communication for upcoming projects and hope to be able to keep using Max/MSP. As I said - I think it’s brilliant software!

What will you be working on next?

I’ve started a company called 3lectromode. With 3lectromode I’m innovating in the field of wearables by combining technology with customizable prêt-â-porter [off the rack, ready to wear] fashion. We are a small group of researchers: Magalie Coulombe-Noël, one of my former students at Concordia has a background in fashion design so we have been collaborating on some projects. We are developing accessible wearables that combine D-I-Y technology with current fashion research. We’ve created kits -- a series of dresses at this time -- which can be bought either as a D-I-Y kit with all the components and a dress which is printed on a custom fabric printer integrating the pattern and the graphics onto one piece of textile -- you just cut the dress out and assemble following the directions. Or it can also be bought pre-assembled. We want wearables to step out of their geeky niche and really be a part of fashion. For example, recently some of the couture houses -- Chanel, for example -- have integrated technological components in their designs such as a light-bulb enhanced heel on a shoe.

I’m also fascinated with the potential for technology to create new modalities of interaction between the body and its environment, so we are interested in the performative potential of technology. The work I’ll be making with 3lectromode will be focused on how wearables can be ‘performed’ and how the experience of wearing wearables changes our every day relationship with the clothes we wear and the environments we engage in. The Futurists were very interested in this, so, I am once again going back to the early 20th century for inspiration. Also with 3lectromode we’re aiming to develop a library of open sourced tools -- ways of rapid prototyping patterns and designs as well as circuits adaptable to wearables -- which can be used easily by anyone to create their own fashionable wearables.

The motto for 3lectromode is: “Creating a future where wearables are democratized, aestheticized, and performative.”

Interview by Marsha Vdovin and Ron MacLeod for Cycling '74.

by Marsha Vdovin on July 14, 2010