Book Review: A Humument

The question of inspiration and its sources isn't necessarily something that comes up often in the Max Forum in any but the most oblique of ways – it’s usually more latent than blatant. Some reasons for it aren't all that surprising, when you think of it: in some sense, every Package Manager download or Projects page posting or even patch grovel can be seen as an inspiration or responses to inspiration. In addition, we're all using a shared programming environment that encourages us to be the person making the connections, and – in the process – owning our “version” of what inspired us. That exchange is a great part of the Max community, really.

Our shared sources of inspiration also tend to group together – in marketing terms, think of those fancy recommendation engines that tell us what books or recordings or products we should acquire next based on what “other people who bought this” do. But what place is there for source of inspiration that “leap the gap?” – those objects or collections of ideas that won’t register in terms of patterns of acquisition?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot in the last month - I was honestly surprised at the response to my recent review Christopher Alexander's Pattern Language – my email inbox filled with personal notes from people in Maxland who were enthusiastic about discovering the book or connecting it to their love of object-oriented programming.

My initial plan was to return this time to to reviews and pointers for what I guess we could call “my basic reference shelf,” (books like this and this and this and this) since it’s been extremely popular. I promise to do that next time out, but I’m going to do a shout-out to one more “sideways” source of inspiration and pleasure and say a few things about what it has to teach us before I go.

It's a book. Or, rather, it once was a book - before it became something else entirely.

You probably know the work of the British artist Tom Phillips even if you don’t know his name – his paintings adorn the covers of Brian Eno’s Another Green World and Thursday Afternoon, King Crimson’s Starless and Bible Black (the original of whose inside gatefold would be something hanging on my wall, were I a rich man) as well as any number of Iris Murdoch’s novels if you're a UK reader. Allow me to introduce you to what is arguably his best-known work: the Humument.

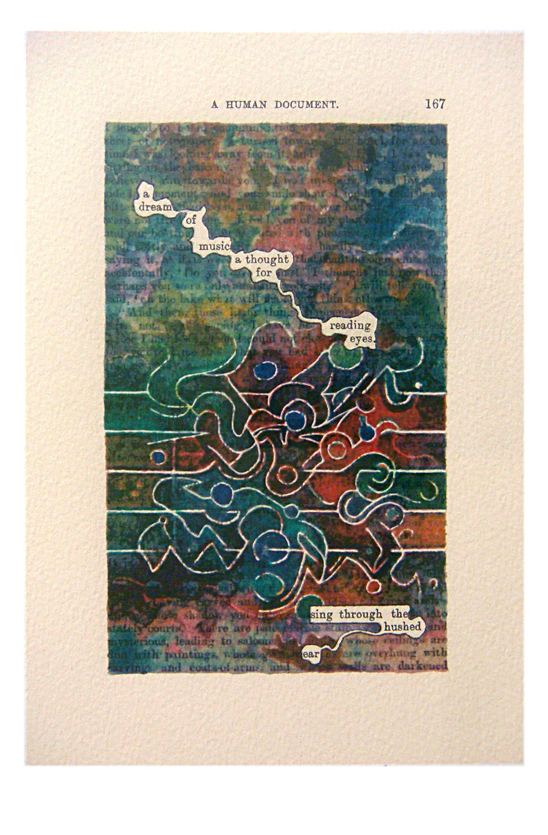

One day in the 1960s, Phillips went to a used booksellers with the idea (hatched with his painter pal R. B. Kitaj) that he’d buy an inexpensive used book and use it as the source material for a piece of art. He wound up with a copy of a once-popular Victorian novel by W. H. Mallock – A Human Document. Once he had the book, he began to draw or paint or collage over the original text and leaving some of the original words peeking through as little bubbles connected by serpentine paths – the Human Document thus because the Humument.

In doing so, he created a “new” text – a story about someone named Bill Toge (whose name appears any time the word “together” or “altogether” appeared in the original) and his pursuit of the mysterious IRMA - the elusive object of his desire (This pursuit, in the form of the opera IRMA, with music and stage instructions and a libretto generated from pages of the Humument, are available as a score, or in several recorded versions - one realized by Gavin Bryars for the Obscure Music label, and one that includes Phillips himself, along with members of the experimental music ensemble AMM).

The Humument is a singular and amazing idea - The only book I can think of that comes anywhere close to the project is Jonathan Safran Foer’s “Tree of Codes,” which takes the German writer Bruno Schulz’ “Street of Crocodiles” and makes a new story by actually cutting away words and spaces on the original page (which made producing the book itself into an interesting technical challenge).

You can look at an interesting presentation of the entire Humument project here, which will show you the original page of the novel together with the works that were created from it. You can also try your hand at doing a page yourself, thanks to a contest that the Venus Fabriculosa website ran earlier this year that includes an actual page of the novel, should you desire. Finally, if you're not inclined to acquire a copy of this wondrous object for yourself, you can always opt for the iPad version (which features a cool I-Ching-like oracle function that I quite like).

My reason for telling you about this now isn’t because the holiday season is coming and that the book makes an amazing present for your unsuspecting cool close friends (although that’s certainly true), but that something amazing is about to happen. The project is now officially 50 years old (Yes, you read that right. Fifty years. No kidding), and it’s finished. In the years following the publication of the first edition of the book in 1983, Phillips has quietly been going through the book again, making new versions of every single page. Subsequent printings of the book have each included new versions of the some number of the initial pages spread throughout the book, and the project was to end once there were two versions of each and every one of the 360+ pages in the original novel. That’s now done – and Thames & Hudson are releasing the final edition of the book, having exhibited the final version in its entirety in the United States and Great Britain.

In addition to it being an amazing and beautiful piece of work worth of your attention, this "treated Victorian novel" got me thinking about the idea of work - the kinds of work we do, patch to patch, performance to performance, problem to problem.

It is so easy to think of what we do as a sequence of things in time, ephemeral or otherwise. Seeing a single kind of "set me a task" problem expand into the work of a lifetime (or perhaps a shorter span, if that frightens you a little) turns the mind away from the idea that the next thing we do is The Big One, and also from the idea that the skills we acquire (say, patching) are merely the dismissal of a set of unrelated obstacles on our way to that Next Big Thing.

Can you imagine a kind of challenge for yourself that you could work at for an extended period of time? R. Luke DuBois' A Year in MP3s project comes to mind here, or Joost Rekveld's investigatory sequences of film/video. Perhaps the act of naming itself can frame the undertaking - Carl Stone's works, though they vary in technique, all take their names from a decidedly quotidian source - the restaurants in which he has eaten over the since he began creating astounding electronic music in the 1970s and 1980s.

When you think of your own work, what insights could you imagine emerging from such a practice? In the case of Luke Dubois’ year in MP3s, he has some particularly interesting things to say about what happens when you work on a project like that. In the case of the Humument, it's interesting to speculate on whether or not Tom saw his humble project becoming a life’s work. He talks about working on it as a little task at the end of his studio day here, in fact - as a kind of regular and patient labor.

If you're not the sort of person who thinks of setting such tasks for yourself, how do you think you might recognize an idea that could contain within itself the seed of a life’s work? In the midst of finding the solution for the task immediately before you, how might you imagine or sense a curve or trajectory or informing kind of interest for your own humble projects? In short, what might an audio (or visual) equivalent of a project like this be - for you?

by Gregory Taylor on November 15, 2016