Book Review: Electronic and Computer Music

Everybody loves secret, hidden, or esoteric histories – even, in my experience, people who don’t like History very much.

I think that’s because we love stories that include us – as privy to stories that only the initiated know, or stories that, by including us and our own experiences, help us to make sense of ourselves. Those stories are implied by the English word history itself (while the word shares an etymological root on the distant past with the word “wit,” we English speakers got it from our 12th century Norman overlords, and it’s got the word “story” stuck in portmanteau word fashion right in there). How do we tell the stories? What do we pay attention to?

When it comes to electronic and computer music, we have ample examples – both in and out of print – of histories that focus on music as a set of works spaced out over time, of histories that cite works or composers as products of or exemplars of ideas (intellectual history), histories that try to capture the ethos of a time or place by means of interviews, and even histories where someone’s personal approaches become an opportunity to reflect upon current practice and/or possible paths to a future.

I could recommend any number of those books to you, and I have favorites of my own. The book review series we've undertaken here on the Forum contains a number of them, in fact. I’d like to talk a little bit today about a kind of history that I think is more difficult to locate: histories of computer music that either focus upon or include discussions about the way in which the tools shape cultural practice. In the case of the work that you and I do in the age of the digital audio workstation (DAW) and the languages/software we use to realize our ideas (whether they’re programming languages or environments or end-user applications or plug-ins), I think it’s worthwhile and interesting to consider those stories that are as much about products and markets and the diffusion of tools through communities of shared practice as they are about composers and works of art.

It’s not hard to imagine why we might not be thinking and writing as much about tools or software and hardware as what archaeologists and anthropologists call material culture. It seems like I talk about this again and again, but those tools tend to be the things we think with rather than the things we think about. When we speak of great electronic tape pieces, we talk about composers. We talk about studios. We speak less about the Tonmeister’s “assistants” or the engineers who developed the tools and hardware. We may talk even less about the tools they created. But for many of us working in the modern DAW/Plug-in/protocol world, the stories and histories of development of commercial instruments are very much a part of our shared history.

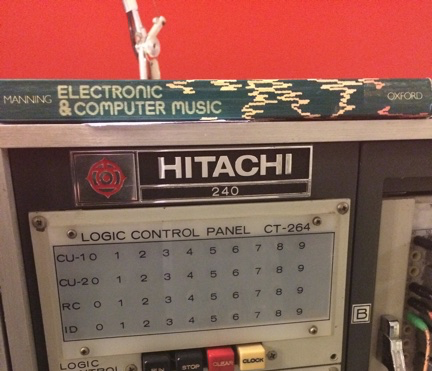

If you’re someone who might find those stories interesting, I’d like to recommend Peter Manning’s Electronic and Computer Music (Fourth Edition, Oxford University Press) as an enjoyable readerly journey.This book has been around for a long time – my old paperback copy dates from the late mid-90s (the book itself has been around since the mid 1980s) sometime, and is considerably smaller than the fourth edition, published in 2013. That old copy served me pretty well. And I’m not alone – during a recent tour of an analog electronic music studio in the Netherlands, I happened to noticed a well-thumbed copy of the same earlier edition sitting right up on top of their Hitachi analog computer – obviously in use by someone working in the studio….

My new edition lives on my Kindle (Living abroad in an environment where books in English tend to be expensive and where I’m going to have to eventually think about shipping things back home has modified my “I love books as physical objects” bias somewhat), and it's great to carry around.

I’ll confess right up front that I was initially sent scurrying to find an updated edition of Peter Manning’s book was a line in a review that many readers might have read differently than I did. I found out about the new edition from a review by my friend James Harley in the Computer Music Journal. His expository prose was ticking along nicely, and included a great listing of precisely what had changed since the last edition, and then my eyes fell upon these lines:

I would prefer to have more emphasis placed on the “music” part of the title, and perhaps less on the technology required to produce that music. Too often throughout the book, it is the evolution of the technology that seems to be the main point….

“Aha!” I thought. “This might be just the kind of thing I’ve been looking for….” (If you’re reading this, thanks, James!). And it was.

In some ways, the 2013 edition is quite a different book than the first edition, which was a more traditional history that focused on composers, studios, techniques and technical concepts. It seems that the practice of “updating” such books to reflect what’s “new” since the last edition of the book encourages that focus on changes outside of composers, works, and techniques. And the updates provide the key to the book’s usefulness, I think. Along with way, the updated editions tried to conceptualize them in light of what came before – the shift to personal computers and laptops, the arrival of digital audio, the effect of those changes on academic and popular music, the arrival of MIDI as a protocol, DAW software and plug-ins, and so on. The result is – for me, anyway, the best book out there that discusses the interplay of tools and techiques in the context of our history – how we got here, and how the tools we use have altered the landscape.

In addition, Electronic and Computer Music does a great job of handling what we might think of as the more traditional history of centers of social and cultural capital, composers, and the technques associated with realizing works. It’s got a nice bibliography/discography section (a website, now, too) for further listening, too.

But for me, the book really shines in the new edition when it traces the relationships between practice and tools and protocols and products, and it's at its best when it considers our communities of practice as defined in interesting ways by the constraints of hardware (which are often constraints of the marketplace), the repurposing of protocols to serve new ends (the migration of MIDI from synthesizer control to more general protocols for controllers), and a stop along the way to describe and contextualize approaches which are either far less well known or notions which did not survive in a market environment. They, too, have a story to tell us.

by Gregory Taylor on April 17, 2017