On The Road: NIME 2018

The Firesign Theater ended their album "I Think We're All Bozos On This Bus" with a forune teller intoning something that I always think of when I try to describe an event or experience to someone else.

Well, the fireworks are over, only the smoke remains....

Reporting on the annual papers, performances and pyrotechnics that comprise the NIME conference is an exercise in making a kind of reduction sauce - in this case, boiling a rambunctious community of persons with the shared goal of imagining different forms for musical expression down into a manageable collection of images, words, and links (I am assisted this year by the NIME folks helpfully putting the entire conference proceedings online, allowing me to link my observations liberally to the papers themselves). What makes the NIME conferences so difficult to summarize can been intuited by looking at the organizational names given to the paper and poster sessions - Collaboration and Audience / Software and Algorithms / Movement and Gesture / Multi-Touch and Haptics / Theory and Critique / Making and New Instruments / Skill, Learning, and Guitars / New Instruments and Interactions / Sound Generation / Robotics and Mechatronics. Each of those could be a conference on its own - so I hope that my problems are becoming clear. But onward, dear readers. Onward.

It was an amazing week - the conference was co-hosted on the Virginia Tech campus by Virginia Tech and the University of Virginia, whose faculties comprise an extraordinary range of diverse talent. That diversity may, in part, explain some of the success of this gathering.

Let's start with some of what we saw and heard.

This year's NIME was interesting for the choice to include href="http://nime2018.icat.vt.edu/keynotes/">a collection of keynote speakers who both spoke and performed during the week. The quartet of keynotes included Ikue Mori, Onyx Ashanti, R. Benjamin Knapp, and Pamela Z, each of whom brought very different approaches, solutions, and idiosyncratic forms of fluency and virtuosity to their practice.

That range of talent and interests really set the stage for the rest of what we heard all week; nearly all of the concerts held some kind of surprise. They struck me as being really inclusive in terms of style and approach, and remarkably well curated. I was surprised at the extent to which I’d start a given performance out staring at the stage and wondering about interfaces and algorithms, only to find myself a minute and something into a piece and watching and listening instead (an example of this for me was Akiko Hakateyama's piece for candles, live voice, and sounds, where I spent exactly 30 seconds playing "spot the software"). In some cases, I was entirely too dumbfounded to remember to take any photographs, for which I apologize.

One interesting feature of NIME is that you often have a chance to see the interface/equipment used in a performance in a paper or poster session, and then have a chance to hear it used in concert, giving you a rare chance to meditate on virtuosity with an instrument that you've actually had some personal experience with.

Alexander Refsum Jensenius and his colleagues in Oslo have been pursuing a twist on NIME instrument design – music generated and regulated by the absence of motion. The MYO armband remains a relatively inexpensive sensor interface of interest to many users, the Standstill ensemble presents a very different view of how to create music in a group – the sense of virtuosity in performance is connected to a very different kind of muscular control (Just in case you had any doubts about the difficulty involved in such a performance, you could strap on their MYO-bela board ensemble in a poster session and discover just how unskilled you are at “holding still.”).

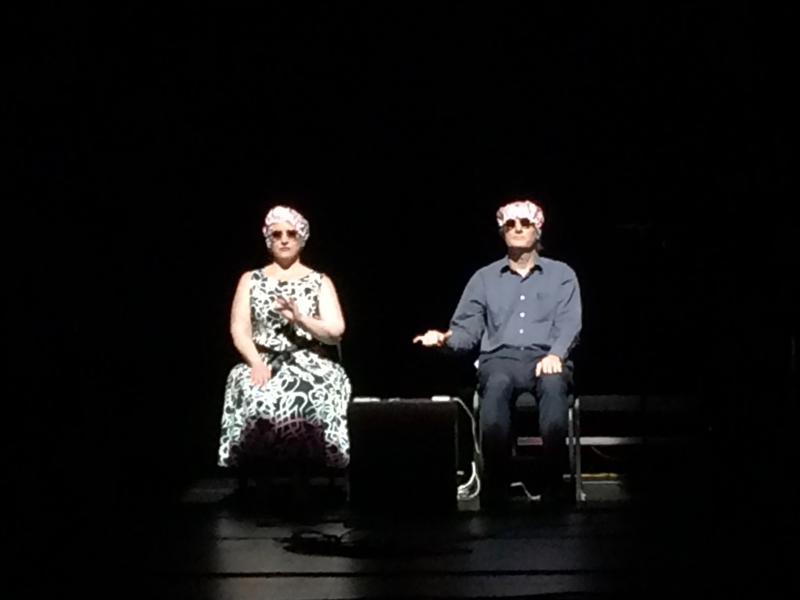

As NIME continues to expand, new faces appear - and some of them are, well... familiar. This was Miller Puckette's first NIME conference, and he enlivened it considerably by providing a diverting bit of virtual thumb-wrestling with Kerry Hagan, complete with shades and Flamingo-patterned shower caps. Watch out, Convolution Brothers! There's a new bunch of kids on the block....

But NIME wasn't all sitting in a concert space being surrounded by awesome. I decided that I was going to try providing a better report on the NIME community by attending closely to the paper sessions this year.

Sitting in the paper sessions starting at 9 AM each morning was largely enabled by a simple but profound courtesy: really good coffee, fresh fruit, and pastries for attendees starting first thing in the morning. This may be responsible for whatever reportorial success I have here.

Despite its diversity of approach and emphasis, the NIME community does orbit each year around a number of attractors which have moved and evolved over the years (for an excellent introduction to the community's basic interests and the organization's evolution I recommend A NIME Reader: Fifteen Years of New Instruments for Musical Expression). One way I might summarize what went down in the paper sessions this year is to report on the topics that engendered the most discussion, and the topics which appeared in the paper titles themselves.

One of the most interesting developments at NIME arrived in the form of discussions about inclusion. As a community, NIME tends to focus on certain ideas over time – in the past, that’s centered around ideas associated with developing a shared vocabulary for instrument/interface design, and creating better ways of sharing data among communities of creators, as examples. This year’s NIME focused on a subject that’s come up before, but this was front and center – the notion of inclusion and questions of representation within the NIME community. It took several forms - Anna Xambo's paper Who Are the Women Authors in NIME? – Improving Gender Balance in NIME Research ran the numbers from 2001 to 2017 and gave us all pause, Sarah Reid's Women Who Build Things: Gestural Controllers, Augmented Instruments, and Musical Mechatronics reminded us of just who our foremothers and colleagues were and are, and a Sunday workshop by Astrid Bin, Sarah Shoeman, and Anna Weisling engaged in practical discussions for building community and working for parity for women and gender non-conforming people, Any of you interested in these discussions should take a look at the Women in Music Technology website as a place to start. It will be very interesting and productive to see where these discussions lead us.

Since NIMEs (yes, it's a noun) are really about converting one form of activity to some mapped output, it's not surprising to imagine why machine learning in general and neural networks in particular would interest creators of new instrumental interfaces.

This year's NIME didn't disappoint in this regard at all. Neural nets helped to train improvising interfaces for ROLI Lightpads and evolvable generators for audio waveforms. While I was fascinated by the machine learning papers, I longed to hear the results of all that training and those hidden models churning away as they listened and learned. I was in luck, this time out. Scott Deal’s “Goldstream Variations” was my first chance to hear Benjamin’s Smith’s ml.star machine language objects for Max (by the way, there's a recent update that adds hidden Markov model and Markov chain abstractions) in some other context than a help file. The harp/percussion duet with Erzsébet Gaál Rinne (while Harry Chaubey slaved away over a stove full of boiling algorithms) was really memorable.

It's tough to attend a NIME and not have your sense of single-word categories stretched and folded just a little. Wanna talk design? Okay, how about strategies for cross-adaptive instrument design for studio and live ensembles, interactive Tango Milonga, or the media archaeology of the typewriter....

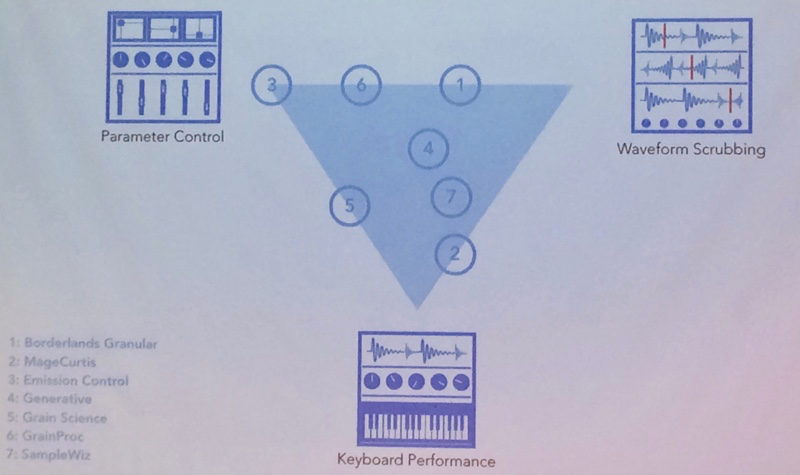

Granular synthesis was on view, as well. When you think of it, it makes complete sense - the range of effects provided by granular synthesis is wide, the results are in no danger of being confused with any obvious acoustic instruments (new interfaces need new sounds, if only to escape the snare of audience expectations in terms of timbre and the construction of new kinds of virtuosity), and there are a lot of interesting possibilities for interface design. Here's one of the more interesting interfaces (and the paper that accompanied it):

Ricky Graham of Delta Sound Labs has a nifty little granular plug-in in development (watch the newsletter for more on this as it develops), too. I left NIME 2018 with not only a list of the possibilities, but a map of the territory, as well.

Quite a full day, huh? Never fear - there were restful breaks in the afternoons when we could spend some serious time tire-kicking and kibbitizing with a few vendors...

playing some interesting and well-made NIMEs to your heart's content...

exploring various forms of actuation...

checking out the latest in fluent wearable interfaces...

and generally marching to the beat of a number of different drummers

And for a break, you could wander over and check out the installations (kudos to Stephan Moore and Peter Bussigel on the repurposing of an antique hotel switchboard as the actuation interface for a gaggle of odd little machines).

Whenever you find yourself feeling responsible for providing the 10,000 foot view of as large and sprawling a conference as NIME, there are also things that fall into the category of “stuff that really excited me personally” that may not fit well into the larger narrative of change and progress. To end, I’ll avail myself of this article to mention a few things that I was personally drawn to.

The Musebots project continues to evolve and refine itself into something rich and strange (to quote the Bard). You really should check this out.

I never thought much about sentiment analysis as a source for interesting music. I do now.

One of the places where I nerd out at NIME has to do with issues related to tuning and timbre. While a bewildering array of polyrhythmic mappings flourish everywhere, I continue to be amazed at the relative dearth of xentonal explorations, and excited by exceptions to that rule, when they appear. In that regard, Bill Manaris and Pangur Brougham-Cook warmed my heart with a poster session that included ancient Greek musical fragments and a Jython-based visual interface for exploring the tetrachordal genera.

Dysfluency as a design strategy? Yes, please.

While we're at it, what about connecting chaotic maps to digital waveguides as an instrumental strategy?

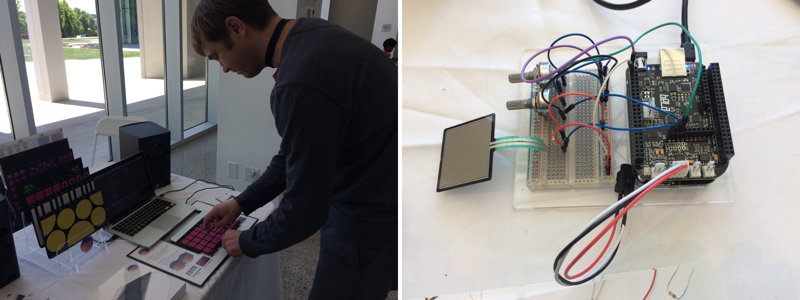

We reported on Bob Pritchard and Kiran Bhumber's work on wearable interfaces in the Cycling '74 newsletter . I had a chance to see it at work in its current incarnation, and I wasn't disappointed.

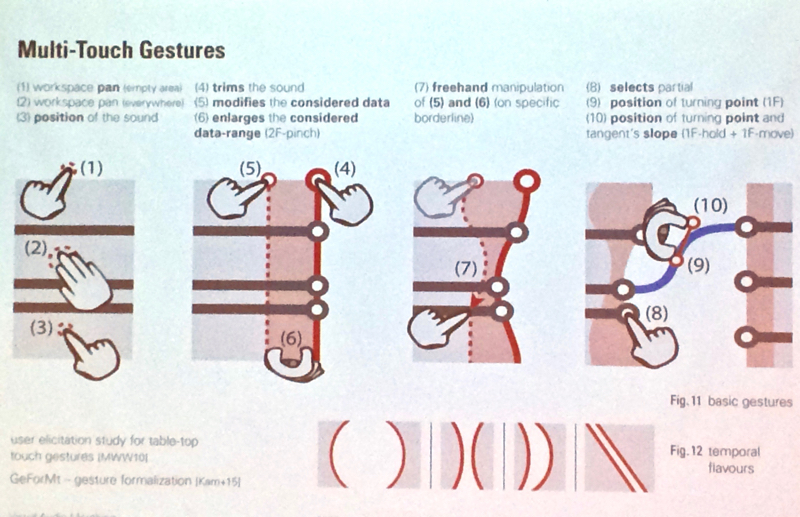

I don’t normally think of myself as someone obsessed with user interfaces and HCI in general, although perhaps I should be. Attending the NIME conference provides the happy opportunity to discover new or particularly elegant approaches to interfaces for interacting with audio material. In this case I found Lars Engeln's paper on multi-touch visual audio-morphing interface to be a particularly beautiful set of solutions.

I really must bring this to a close somehow. It was an exhausting and wonderful week, and I'm sorry I didn't see you there. If I forgot something amazing you saw, add your comments below. If you were there, I'm sorry we didn't hang, or hang more. And I still owe you that pint (you know who you are).

One way to get a sense of what happened that I didn't mention would be to head over to the online archive of NIME proceedings. This year's conference listed at the top, so you can scroll down through the paper titles and spend some quality time chasing your own interests down.

I hope you get a sense of why this is/was an amazing place to be. Oh – in case you’re wondering, next year’s NIME conference is going to be hosted in Porto Allegre in Brazil. Time to brush up on your Portuguese!

Gregory

by Gregory Taylor on June 19, 2018