An Interview with Ryan Holsopple

One of the most wonderful aspects of Max is that is used by artists of all disciplines. Ryan Holsopple is working in the space between theatre, performance and film and while his work employs Max on a most sophisticated level the extent of the technology is invisible to the audience. Perhaps after reading this article more people will start using Max for multimedia show control.

Where are you from originally?

I’m from central Pennsylvania. Hershey, Pennsylvania. That’s where I went to high school.

Were you a creative child?

I guess. I was always into performing and acting. That’s what I was trained in as an undergrad. I was always involved in theater, in the school, in that creative realm. I went to East Carolina University, in North Carolina, for acting.

Once I was in that program I realized, “Oh, I can do all this stuff with interactive, telecommunications in performance.”

How did you make the transition to performance art?

That school was more traditional in its approach to acting training, but I was always more interested in experimental theater. So when I moved to New York in ’95, I basically immersed myself in the experimental-theater world and performance there.

I saw Richard Foreman’s work. I was blown away by his work, and eventually got a chance to work with him a couple of times and do theater in the downtown New York scene. That was a lot of fun.

Then I was working with somebody who was applying to the ITP program at NYU [Interactive Telecommunications Program], so I decided to apply to that. I ended up going back to grad school kind of later in life, hoping to find another job. Theater arts just wasn’t that lucrative.

Once I was in that program I realized, “Oh, I can do all this stuff with interactive, telecommunications in performance.” So I kind of got back into that world. I never really escaped it like I intended to.

Are you naturally technical person?

Well, I knew technology through working on pinball machines, radios, and Super 8 films. Those were all my interests. But those were more electro-mechanical and analog. I think I got my first computer in 2001 — an iMac.

Then, when I went into grad school, I started learning more definitively about what was going on in the current state of technology. I learned how to program micro-controllers, and learned the difference between analog and digital in a very hands-on kind of way.

...search, look up, and learn from what other people have done.

How was your experience learning Max?

I’m basically self taught. I never took an actual class at NYU in Max, but in my first class there, Physical Computing, we were learning to program micro-controllers—this was before Arduino had hit the scene. Some of the people in the class were from the Music Tech program and they were using Max. That’s when I first caught a glimpse of it.

We used Max for a group project in that class. I worked with Mirit Tal, who was to become a longtime collaborator of mine from that project on. We took a marionette with an accelerometer on its yolk that moved the marionette around. Basically, it could navigate its way through a time Quicktime VR, using Max. So that was our first Max project and from then on it was like, “Oh, this is a lot of fun — and handy!” [Laughs]

I never really went step-by-step through the tutorials. I just would come up with projects, and would just use it, figuring out as I went how to program with it and so forth.

Get stuck, look it up!

Exactly, especially with all the online resources. I think that the thing I came away with the most from the ITP program was how to search, look up, and learn from what other people have done.

I think a lot of people can be intimidated by Max, but it’s actually a lot less intimidating than writing code. I find it kind of soothing, actually.

[Max] is like the brain center.

Which of your works use Max?

All the performances. I’ve often thought about uploading all the patches from older shows, so people could perform the show again, like it’s a script or a score or something.

Basically, I’m using it as a show control. That's kind of my approach to Max. I’m a sound designer, but I also control all the elements of the theater through Max. So it’s like the brain center.

I used Max originally so I could still perform on stage. I didn’t want a stage manager or anybody cueing the show, because that’s too difficult to bring somebody in for free to do that kind of work. So Max is an easy way for me to be able to control it from the stage. By using switches, sensors or buttons from the stage, and I could retain control the sound and lights.

The most recent performance I did, called Here at Home, was a heavily Max programmed piece. It also had a lot of surround sound using the z.abstractions from Zachary Seldess, which enable you to use it with multichannel audio, and move the sound around the space.

There have been a few articles recently using DMX and Max, which I think is exciting that people are doing that more, in the show-control world. That you can actually run a show, sound and lights and everything. And these theaters have all this technology, and you can kind of tap into that.

So, you use Max primarily for performance work?

I basically have two modes of how I’m using Max. One is with the theater company, where everything is based on Max. But also I freelance as a programmer for other people as well.

Some of the projects that I posted on the Cycling ’74 web site are where I’ve programmed using Max for other people’s projects.

Can you give us an example of how you applied your Max expertise for other clients projects?

A recent one, The Shooting Gallery that’s up there, that I developed for artist Bill Morrison, with composer Richard Einhorn. He wanted to have the audience enter a space with laser pointers so they become the controllers of what films they see.

There are four screens that show the films, comprised of archival footage that Bill manipulates. So the audience members would come in with laser pointers, and like an old-time target range, they would use them to ‘shoot’ at targets on other video screens to choose which video was played — a pretty chaotic, wild time. It was at BAM, the Brooklyn Academy of Music this past November.

That was a heavy, heavy Max programmed piece. Four cameras had to go on the targets the people were pointing at with laser pointers, and then basically when they hit targets with the laser pointer, I had to know when that happened, and how to activate video with it. I had to use a six-computer system.

I was using the Computer Vision library from Jean-Marc Pelletier, the cv.jit tools. I was basically looking for the brightest pixels, so the laser pointer was always brighter than the image. It also counts, from brightest pixel on down. It will track those on the screen and assign it a number. Then I could do things like count how many laser pointers were on a screen.

We even had certain parts of the show where people had to work as a group together. The more lasers were all on one screen, the more affected the video on other screens. It’s kind of a learning process with immediate feedback.

It’s really fun to create a piece that was interactive, that people had to figure out how to use it and work together as a group.

I use [peakamp~] to look at the sound wave and get numbers out of that, which can port right over to lighting or video or anything really.

Do you ever write your own objects?

No, I don’t write my own objects. I usually can find one to fit the bill. If I come up against a wall, there's always someone who has already, for the most part, solved it. Which is great.

Do you have a favorite object?

I really like the peakamp~ object, which I use because I do a lot programming where sound controls lighting, or sound controls something. I use it to look at the sound wave and get numbers out of that, which can port right over to lighting or video or anything really. So I use peakamp~ a lot!

Artists that I work for are always really into random. So I use the RTC-lib, the Real Time Composition library by Karlheinz Essl. He has a lot of very cool, random abstractions.

Any chance to make something more random is always desired! [Laughs]

I built a scream-o-meter with Max, that measures the pitch and loudness of the screams.

How are you going to challenge yourself in the future?

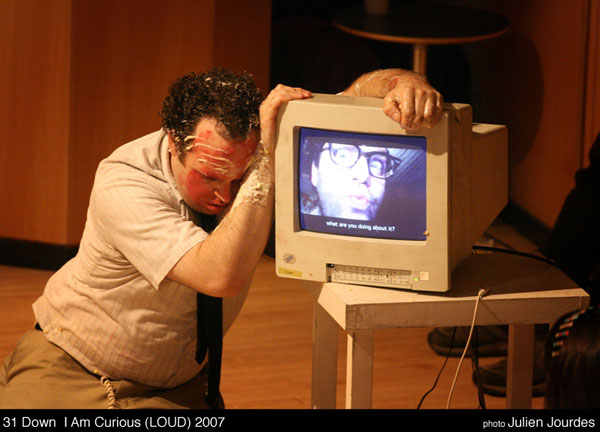

That’s a good question. We have 31 Down, the company that I started for interactive performance and installation development.

We have an interactive installation that we did a few years ago at this rock and art festival in Seattle called Bumbershoot. Basically it’s a screaming contest, with a live band playing on stage. People from the audience can come up and read a radio-theater scene with me behind a screen while the band plays — and it always ends with a scream!

It’s called The Scream Contest and is based on how high and loud you can scream. I built a scream-o-meter with Max, that measures the pitch and loudness of the screams. Kids usually win it, because their screams are incredibly high. But it’s an installation for the whole family, which I think is a lot of fun, because kids like to do it.

Sounds like good family fun! [Laughs]

It really is!

There’s an old Marine base in Orange County that has an old World War II hangar, and we’ve been asked to come and do the Scream Contest coming up in March. The big challenge is how do we fill that space, but also make it sound really great and get people to scream so we can measure it.

And then I have a show next fall, with 31 Down, where we’re trying to use hypnotized actors. I guess the idea around it is; can you control performers like you can a light? Can they become an object that you can turn on and off, and can you manipulate them through hypnosis to say, to turn around or to cry?

So it’s still in the full-on experimental stage right now, I don’t have the answers yet.

How do you purpose to use Max to communicate these instructions to the hypnotized performers?

Well, my instinct is through sound. Of course, they could wear an in-ear receiver, where somebody can actually talk to them through it. But my first thought is to trigger a response through sound. There are frequencies in the audio that the human can hear, and certain frequencies are attached to different emotional colors. The audience might not perceive the frequency as anything but part of the sound design, but the performers on stage could be attuned to them.

So for instance in Max, I could send out a certain frequency of sound wave amongst a sound design, and then the performer hears that and turns to the right, or cries.

It’s all based on the hypnotist, so I don’t know exactly if it will work. But that’s what we’re trying to do in the future. I think it will be fun.

I just want to keep treading new territory…

Text interview by Marsha Vdovin and Ron MacLeod for Cycling '74.

by Marsha Vdovin on June 10, 2013