Collaborative Performance with Node for Max

What can you do if you’re not that interested in streaming work during lockdown but the opportunities for gallery or festival performance are still out there? If online exhibitions seem a pale substitution for being together in the real world, can one create something using the tools one has to create something that’s different rather than an attempt to copy the real world?

Mark Fell and Rian Treanor, together with their students at the Hochschule fur Gestaltung in Karlsruhe, took on this question together and enlisted Node for Max to help them think differently.

Darwin Grosse:

Let's start by talking about the project: what it is that you're trying to accomplish, and what's the artistic intent?

Mark Fell:

Well, basically, it's a response to the situation that we find ourselves in - the whole lockdown thing. Lots of festivals and galleries are getting in touch saying, "Can you do this online thing?" And we were both not very happy about streaming or anything like that. Online exhibitions as a substitution for real world being together - it just didn't seem very good, so we were like, "What can we do that is a meaningful response to this situation that actually uses the technology to create something that is different than just a copy of the real world situation?" So that's the kind of artistic intent, I guess.

Rian Treanor:

But also, you were working with the students in Karlsruhe, and you were discussing about, "How is this impacting our creative practices and what things can we do in this context that enables other kinds of work to be made?"

MF: I'd been doing this job at Karlsruhe. Hochschule fur Gestaltung, HfG. It's next to ZKM, the big media office. So, basically, I'd gotten a job as guest professor in sound and media art. And I'd been doing it last semester, and this semester starting in March/April came along, and I thought, "Well, they're going to cancel the contract, because no one can travel." And then they said, "Well, would you want to do it again and do it all online?" It was basically the day before the semester started, and I was like, "What the hell am I going to do? I know. Let's just use this as a way of having a dialogue about what we should do in response to our situation." So the kind of class that I ran was called Dislocational Practices: The Ethics and Aesthetics of Dislocation. So we'd have discussions, and try things. And it was a nice test bed just to throw ideas around.

DG: Yeah. Did they come up with a class after the isolation, or was that already an existing class that just happens to mesh pretty well with our lives?

MF: Well, the group was already there. I had to come up with a name of a program.

DG: Well, it's interesting, because so many programs have classes on location-specific art, and it's kind of interesting to think of the twisting that or putting that on its ear by saying there's dislocated practices as well.

MF: Yeah.

DG: Now, one of the things I think is interesting is sort of the idea that you're trying to do something that extends beyond just attempting to reproduce the standard performance or the standard installation. Rian, you actually do a lot of performing. What is your influence on this project, and is it something you're hoping to solve an equation for your work?

RT: Yeah, partly, but also I've been doing lots of collaborative projects over the past few years, and also doing quite a few workshops with young kids - or people that are not necessarily trained musicians. So I've been doing a lot of workshops and been specifically wanting to do that more in Rotherham where I am, where I grew up. So over the past two years, I'm like, "Oh, I really want to focus a bit more on..." and now it was just, "Oh, it is actually an ideal time to..."

DG: To focus on it. Right.

RT: There is an opportunity there for these collaborative projects, but also doing a workshop element to it, and that also be a performance and it's not necessarily one person being onstage saying, "Look at me," or, "Listen to what I'm doing." People are actually involved and participating in the thing that's happening together.

MF: Part of this network system is that we don't have to stick to "I'm the performer, you're the audience." I mean, we can stick to that, or it could be that, or if there's audience of 200, five people out of the audience take part in the participation of the piece. Or it could be a traditional "I'm the performer, you're the audience" sort of relationship. But I think what's interesting is that when you start to deal meaningfully with networked systems, those kinds of categories are necessarily challenged. So the kind of classical categories that we have in the art world, and the models and ways of describing the different things that are going on, I think once you start to engage meaningfully in what network systems can do, that means challenging those kinds of categories.

RT: Yeah, or even like, "Oh, there is a possibility to do a slightly different route or something."

DG: The fact that it may open doors for different kinds of art when the delineation between artist and viewer is blurred.

MF: Yeah. It seems to encourage that kind of work, I think. For me, anyways. It's less about the streaming paradigm. "I'm an artist, and I'm streaming my thing on YouTube..." really reinforces the kind of classic audience situation. "I'm the solo genius, and you're the audience. Look at me doing what I do really well."

RT: It's like a piece of artwork behind glass in a museum.

MF: Yeah. It's exaggerating what was problematic about a lot of the traditional art forms and making it even worse. When those art forms are put in an online context, it's like the barrier is amplified. So I think we were thinking, "How can we use this to break that down and do something that isn't about just transplanting classical forms and ideas into an online format? What else can we do?" So I guess from a technical point of view, we're not actually doing anything particularly groundbreaking. Obviously, you [Cycling '74] did some work on these systems, and the infrastructure kind of exists. What we're doing is using that as a way of exploring our kind of creative ideas about how networks and people can function in this context.

RT: It's specifically coming out of this situation where, "Oh, we're all isolated. We don't have any physical connections." And what is really a unique situation that no one's ever experienced it. I guess it makes you think, "Oh, what are the things that we're missing, or what is the thing that is something that we value, and that we participate in." So it's responding to this situation. Previously, we would have just said, "Oh, we've got this idea for remote collaborations." It actually seems just a bit more relevant to explore for us now, because obviously we're totally disconnected from everyone.

MF: Yeah, this is the first time in the history of the human race where the vast majority of people have gone into some form of isolation and lockdown.

RT: What's even weirder is that we're totally connected digitally.

MF: So we're in a very strange situation, I think.

DG: Well, it's interesting, though. One of the things that's difficult about streaming as an artistic expression, is that it's extremely active for one person, and it's extremely passive for everybody else. And what you're talking about actually allows for... It doesn't maybe have to be completely active on everybody's part, some people may choose to be passive about it. But it does seem to open the door for there to be some level of activity. Because if you go to watch somebody perform in a club, you're still active; you have to get in the car, go park, get in the club, pay your 10 euros or whatever, get in there, interact with all the people in the club, buy a drink, all that kind of stuff. There's activity involved. It's not like sitting behind a screen, holding your chin up, and watching somebody do a thing.

MF: Which actually adds to a sense of isolation, I think.

So the question is: "What kind of activities can we try to do?" So before lockdown, I'd become interested in how groups of people can interact in a performance context, so I had kind of gone from a solo performer... I mean, I'm not even from a musical background. I studied film and video at university, experimental media, but was always interested in electronic music: house and techno, not the academic sort of electronic music at all. I'd kind of moved from that to thinking, "How can I do..." I got really interested in how people perform together. We went to India, both of us, and studied Indian classical music and looked at ideas about systems and performance. Because that's what a lot of Indian classical music is. It's very systematized logics that are engaged.

So I'd been coming up with ideas for group performances where certain parameters are given. Very long-form durational performances that might be three or even six hours long. And kind of charting out some structure about how people might interact within that. So one thing I did with the students in Germany before this semester, the previous semester before lockdown, we just did experiments about moving speakers in space as part of a performance. There were 10 students. They all had 10 sounds, 10 speakers. And there was a procedural thing where we each take turns moving a speaker around. And it was a way of structuring group participation that seemed to really work.

So I really liked the idea of performance as not some kind of theatrical expression, but just more performance as procedure. So in the history of like avant-garde art, you have like Fluxus and stuff like this. Bruce Nauman did an early piece called Manipulating the T-Bar. And it's just him in his studio moving this metal bar around in quite a boring way in different positions. So I'm kind of quite interested in this idea of performance as procedure. It's those kinds of ideas that I'm trying to bring to the networked work that we're doing.

RT: Yeah, I guess he's thinking about what kind of systems could you put in place to enable meaningful interactions, or musical outcomes. So, it could be that if player one does this, other players can do that. Basically having a mechanism or system or process in place for people to interact in a way that's not just a total free-for-all. From my perspective, you can still do something that's fun or listenable.

MF: Let me give an example. So I had this group last week, we were supposed to be meeting in the Pyrenees to do some workshops and that was impossible. So I had a group of 25 participants that were distributed over the globe, and I decided to try some of this network stuff. It was several interlocking rhythms of different durations, and all the participants could play on each of the interlocking rhythms. So imagine you have a rhythm that is three elements long and a rhythm that is four elements long. The way they're structured is they kind of fit together like the wheels of a cog, rather than lining up directly.

There was a rhythm that was 11 elements long, one that was 13, 7, 9, I think. And my idea was let's see what people do with this. We managed to get it working, I distributed it to the group, and we all started to just play. And it's really nice just to... You've got your video conferencing thing turned off, and all you can see is other people moving dials and pressing buttons and stuff. It's quite a nice feeling. And you get a sense of, "Wow, we're kind of starting to feel each other's presence," and you start to work with each other. I can see, "Oh, yeah, when I do this, this guy's doing this, and et cetera.

RT: They are actively responding in real time.

MF: And then I said to the group, "Hang on a minute, let's do it so that at any one time, only three... Imagine you got a grid, a Live grid-type thing, which is controlling the rhythm. And let's agree that at any one time, each of these four Live grids can only have three ticked spaces in it. So three events within the Live grid. So this is not something that's imposed by the interface, it's just a rule that we agreed to as a...

RT: A performance.

MF: Yeah. An agreed approach to how we do this. And as soon as we agreed we're only going to have three dots in this Live grid, any one of the four Live grids can only have three dots, as soon as we agreed that, it actually got lot better. Not only musically lot better, but more engaging. Do you see what I mean? Because there was this layer of...

RT: More consideration.

MF: Yeah, there was more consideration. It became more of a meaningful engagement.

DG: I imagine, too, that it forced people to embody being a listener instead of just a knob-turner. And that can be a powerful part of the whole experience. Now, let's talk a little bit about the tech behind the process. You make it sound like there's a singular interface that everybody is able to manipulate simultaneously if they choose to. Is that how that operates?

MF: Right now it is, but it doesn't have to be like that. Right now, we've got it that every user has the same interface, and it might be that we agree, "Okay, User 1, can you just stick to line one? User 2, you just stick to line two," et cetera.

RT: You were doing that into the project for that specific group and for that specific project, but I'm planning a few workshops. One with young kids for this project at the No Bounds festival in Sheffield. That was a completely different system, but using the same kind of...

MF: It's the same gears under the hood.

RT: But it's a different musical interface.

DG: And so, what you're doing is you're defining a user interface that participants operate. And then, what? Is it using Node for Max to communicate with a central server entity?

MF: Yes. So basically, the way we've got it right now is: let's say there are 25 people all logged on. They all log onto the server. The server sends every message from every single user to every other user.

DG: Okay. So it does propagate all the way back out.

MF: It's not like it goes to the server, and then there's some routing, and this message goes to that player. It's like all the server does is just basically pass everything to everyone.

DG: Oh, so actually the sound generation happens on everyone's local computer, too.

MF: Yeah. So the engine is running on your computer, basically. And we're just passing parameters that change the structure of the pattern.

DG: Got it. So now, in a lot of cases, when people they imagine doing collaborative performances on networks - whether it's using something like NINJAM or something else - the sort of obsessive worry that everyone has is, "Oh, latency is a problem. How do I interact rhythmically with someone else when there's no way to have a real-time interface?" How do you deal with that? Or do you just allow that to be one of the structural pieces that individuals embrace?

MF: Well, first off, because the pattern is being generated locally, there's no kind of delay that happening. So what could potentially happen is that... Imagine it's a rhythmic grid and it's looping around. And a message arrives on my computer, and it arrives a few moments later on someone else's computer. And it might arrive in time for the "playhead" to play it mine, but it might arrive moments later on another person's computer, and the "playhead" misses it. So that might happen. Strictly speaking, we're not entirely sure if we're listening to precisely the same thing.

In various ways, it's always been pretty accurate. And also, if you're doing things slightly more like algorithmic musical processes, all it is is basically sending lists of patterns and stuff like that.

RT: As long as people are sharing the same sequences or lists on average, it's really synchronized.

MF: There are two things that should be said about this. Firstly, if there is a delay, the delay from what we see is milliseconds. It's very fast. But even if the delay was worse - actually, from my point of view, that's not a problem. If I've got a CGI model of a tree swaying, and some leaves are slightly different here to this other person's CGI model of a tree swaying, we're still essentially looking at the same kind of tree swaying. Do you see what I mean? Some of the details might be slightly different, but I think we still assimilate the same form. But having said that, the messages arrive so quickly that it's not an issue. But even if it was, for me, it's not a problem. It's not a drawback.

RT: Also, for using MIDI-like patterns, it's really works.

MF: What we're talking about is a procedure that generates patterns that trigger sounds. So we're just sending data to the pattern generating system that then triggers the sounds. So actually it's not MIDI - I need to clarify that.

RT: It's a sequence of events.

DG: So now, you talk about having the nuts and bolts behind this thing being standardized, but having different implementations. Mark, for one exercise, you did an implementation that sounds like it was oriented around grids and rhythmic patterns and stuff. But Rian, now you're talking about doing something for kids to interact with, which is probably going to have a very different interface, and if not... Well, I don't know, maybe it is simplified?

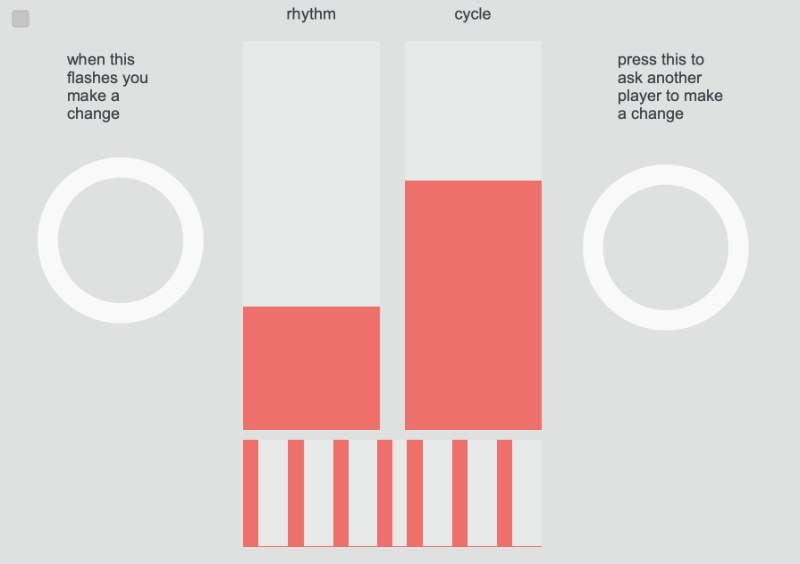

RT: The interface for this project with the kids is actually a step sequencer. And there's a few different parameters, like pitch change or different lengths of notes, and stuff like that. But I'm also doing a project with this elder care home in France, and that is going to be a very different system, where it's more just moving dials rather than any kind of a grid system. So it's partly Euclidean patterns.

But the thing that I think is interesting about that system that it'll be, you've got a message on your left that says when this box's color is red, you make some changes to your pattern generator. And then, if you want somebody else to make changes to their pattern generator, press the button on the right. It's really like a very basic structure. I've not tried it yet - it seems like it should come up with a nice outcome, but I'm not sure.

MF: But that's a really interesting way of having some kind of regulatory mechanism within group behavior that could be sent. I mean, thinking about other game-like dynamics, like chess for example, it's the shared understanding of what you can do when that gives the game meaning. With the pieces and the chess board, you could actually do an infinite number of different things. You could think of lots and lots of moves. You could do totally random stuff. But what gives it meaning is the shared understanding of the kind of interaction that that facilitates. There's a set of rules that stop it from breaking down into just chaos and randomness.

DG: As I think about this, I originally was just thinking about the shared performance aspects. But when all of a sudden you're also talking about having a shared communication protocol where I can pass the baton to somebody else, or prompt somebody into becoming an active participant. That starts bridging into what it's like when you're in a room actually collaborating with someone, because those kinds of communications are almost just as important as: "Here's the notes I'm playing. What are the notes you're playing?"

MF: I think with any form of collaborative music-making, what makes the distinction between something that is successful and something that sounds rubbish is how people are attuned to others in the room. A very bad kind of jam session would be me going, "This is ace!" and I'm just continually freaking out, doing my own thing. Rian's thinking, "This is ace!"

But "Good" is when there's a locking together of different people. And actually, in Indian music... We met this guy who's a South Indian percussionist, and he's very familiar with Indian classical music performance and also improv. He studied in New York, so he's also quite an accomplished kind of improv performer.

And he said something interesting. He said, "When you play with the improv crowd, it's like parallel monologues. But when you perform Carnatic music," (Carnatic is the southern Indian style of classical music), "you and the other people on stage aren't engaged in parallel monologues. You become part of one thing." And that's the kind of mode of improvisation and performance that I'm really interested in. You actually join and become part of a cohesive, singular entity that is a composite of all the elements.

That for me is the interesting thing. It's about building the systems that facilitate that sense of the presence of other people.

I was talking to this guy, a friend of mine, Ernest Edmonds, who was one of the first computer artists, and someone who is quite interested in networks. I was talking to him at the beginning of the lockdown, and said "Ernest, I'm really into this idea of ambient togetherness. Ambient togetherness - like sitting in a train station and just knowing there's a few other people dotted around. How does that happen on a digital platform?" So it's that kind of ideas about kind of how presence is felt that I'm kind of interested in.

For More Information....

If you're interested in realtime communication using Node for Max, you'll probably find Andrew Benson's Node for Max recipe Node Recipe 00: Socket Drawings a source of inspiration and guidance. Mark, Rian, and their students certainly found it to be a great jumping-off point.

by Darwin Grosse on October 27, 2020